What is it?!

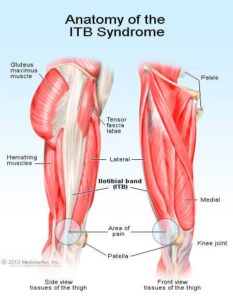

Overuse injury associated with pain on the outside (lateral) part of the knee

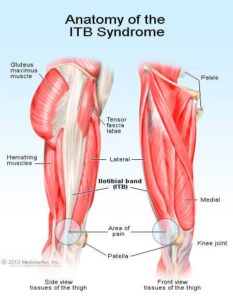

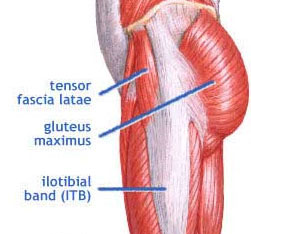

Anatomy

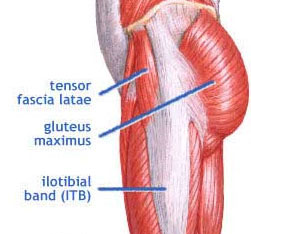

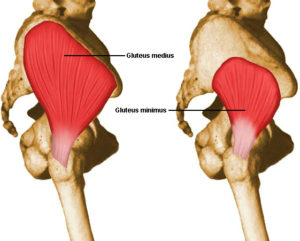

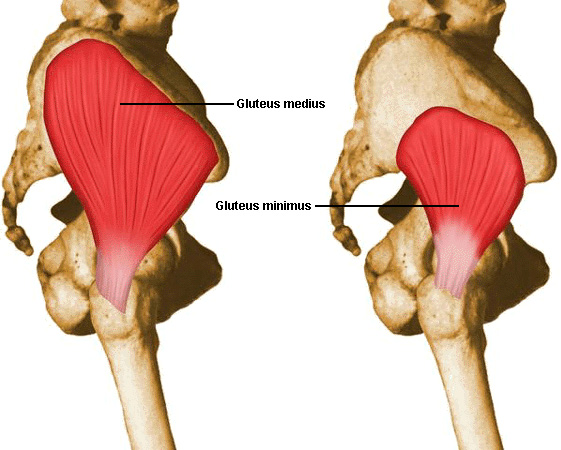

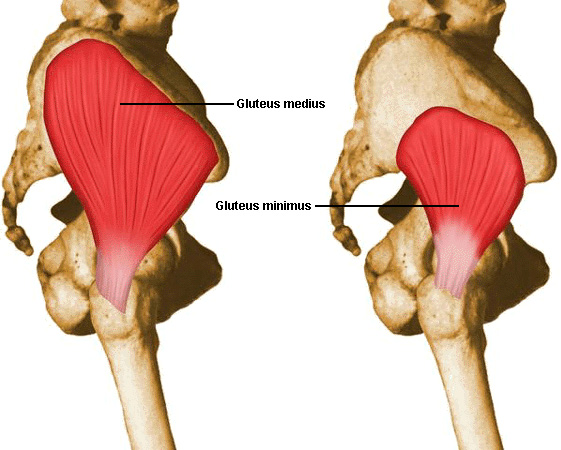

The ITB is a band or sheath of fibrous connective tissue that surrounds the muscles on the outside of the thigh and crosses both the hip and knee joint. It originates from the tensor fascia latae (TFL) and gluteus maximus muscles and then continues down the femur (thigh bone) where it attaches to both the femur and tibia (shin bone) on several bony landmarks.

The function of the IT band is to stabilize the hip and knee as well as limit hip adduction (leg moving towards the midline) and internal rotation of the knee.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The knee is the most commonly injured area in runners – accounting for 25-42% of all running injuries. ITBs is the second most common knee injury for runners with patellofemoral pain syndrome being first.

Signs/Symptoms

Signs/Symptoms

Runners usually have no exact history of trauma and find that the pain comes on gradually over the outside of the knee during a run. The pain usually appears within a few km of a run and increases in intensity. That same area can also be tender to touch.

Pathophysiology/Etiology

There are a couple theories on the pathophysiology of ITBs.

Some researchers believe that ITB inflammation is a result of excessive friction between the ITB and the boney prominences which occur when the ITB slides over the boney structure and causing inflammation during repetitive movements such as running. Others have argued that rather than the ITB band causing excessive friction, the inflammation is caused by the ITB compressing an area of highly innervated fatty tissue between the IT band and boney prominence

Contributing Factors to Developing ITB Syndrome

The most common factor in developing ITBs is an increase in exercise intensity through mileage, hill training or speed work.

Other reported possible causes which may increase tension in the ITB by altering hip and knee angles include:

- Downhill running

- Wearing old shoes

- Always running on same side of road

- Leg length discrepancies

- Excessive pronation of the foot (foot rolling inward)

- Tight ITB

- Weakness of glute medius muscle

ITBs and Running Biomechanics

It has been suggested that injuries can manifest as a result of an increase in exercise intensity beyond a threshold level, combined with certain intrinsic factors in athletes.

A recent systematic review looked at biomechanical variables and investigated whether distance runners who suffer from or develop ITBs have different biomechanics than runners who do not develop ITBs.

The evidence shows that it is unlikely that abnormal biomechanics at the foot or shin bone can contribute to increasing tension of the ITB.

The results suggest more is happening at the hip and knee. Runners who eventually develop ITBs have more internal rotation at the knee and greater  hip adduction angles during the stance phase of running (when the foot is in contact with the ground) compared to healthy controls.

hip adduction angles during the stance phase of running (when the foot is in contact with the ground) compared to healthy controls.

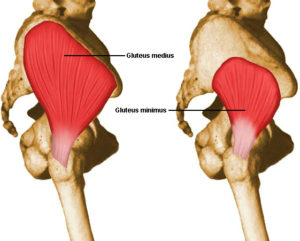

Some researchers have found that this internal rotation of the knee is due more to an externally rotated femur (thigh bone rotated outside) and suggests this may be due to insufficient activity in the medial rotators of the hip (gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, TFL).

As for muscle strength and endurance, there is currently no evidence to suggest that reduced muscle strength plays a role in ITBs. However, the research is limited because many of the trials give inaccurate impressions of a muscle’s functional strength. Future research is needed to look at the timing of muscle action rather than the magnitude of strength.

Research also suggests that runners with current ITBs tend to have more trunk flexion than healthy controls. It is uncertain whether the increased trunk flexion is due to a tight ITB or if the ITB becomes tight as a consequence of the flexed trunk (aka: the torso leaning forward)

How do we treat it!?

Stay tuned to my next article on the latest evidence for treating and managing ITBs!

References:

Foch et la. Associations b/n IT band injury status and running biomechanics in women. Gait & Posture. 2014.

Louw & Deary. The biomechanical variables involved in the aetiology of iliotibial band syndrome in distance runners – a SR. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2014

Signs/Symptoms

Signs/Symptoms hip adduction angles during the stance phase of running (when the foot is in contact with the ground) compared to healthy controls.

hip adduction angles during the stance phase of running (when the foot is in contact with the ground) compared to healthy controls.

It’s a topic I wrote about briefly in the past, but this week I wanted to take a closer look at things. Two strategies I discussed before were (1) getting acclimated to the heat and (2) pre-cooling.

It’s a topic I wrote about briefly in the past, but this week I wanted to take a closer look at things. Two strategies I discussed before were (1) getting acclimated to the heat and (2) pre-cooling.

ed), gluteus maximus (GMax), gluteus minimus (GMin) and TFL (tensor fascia latae). The focus of this article is going to be on the gluteus medius because of its important role in stabilizing the pelvis.

ed), gluteus maximus (GMax), gluteus minimus (GMin) and TFL (tensor fascia latae). The focus of this article is going to be on the gluteus medius because of its important role in stabilizing the pelvis.

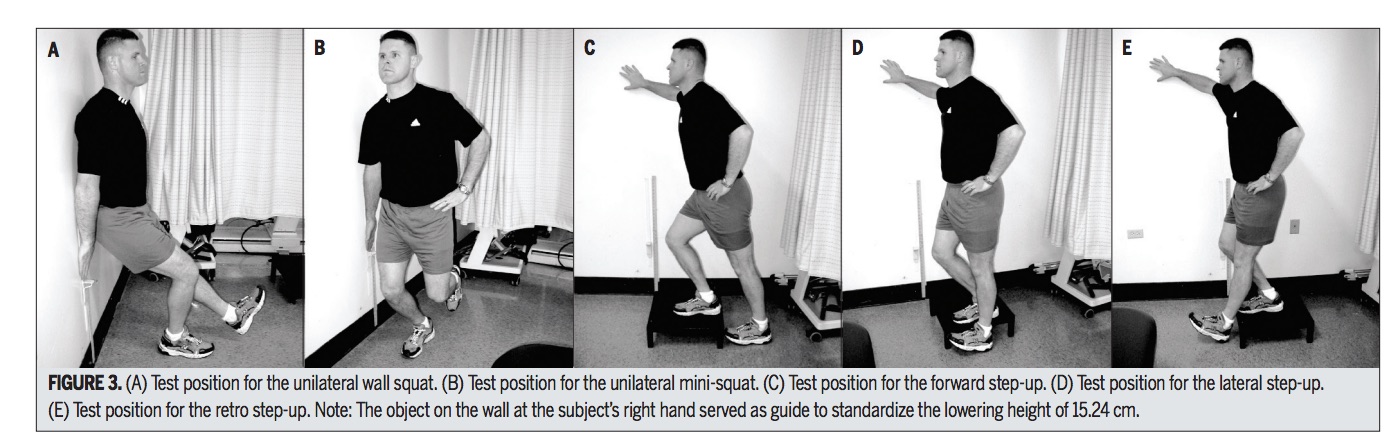

Study #3: What happens when the gluts are weak?

Study #3: What happens when the gluts are weak?

munology notes yet again to relearn what I already know (it’s always fun picturing the T-cells destroying the bad stuff). Times like these also motivate me to relearn other things, like how nothing gets rid of a cold other than some basics including: sufficient rest, fluids, stress management and a good diet.

munology notes yet again to relearn what I already know (it’s always fun picturing the T-cells destroying the bad stuff). Times like these also motivate me to relearn other things, like how nothing gets rid of a cold other than some basics including: sufficient rest, fluids, stress management and a good diet.